The Dirtbag Billionaire who Gave It All Away for Planet Earth

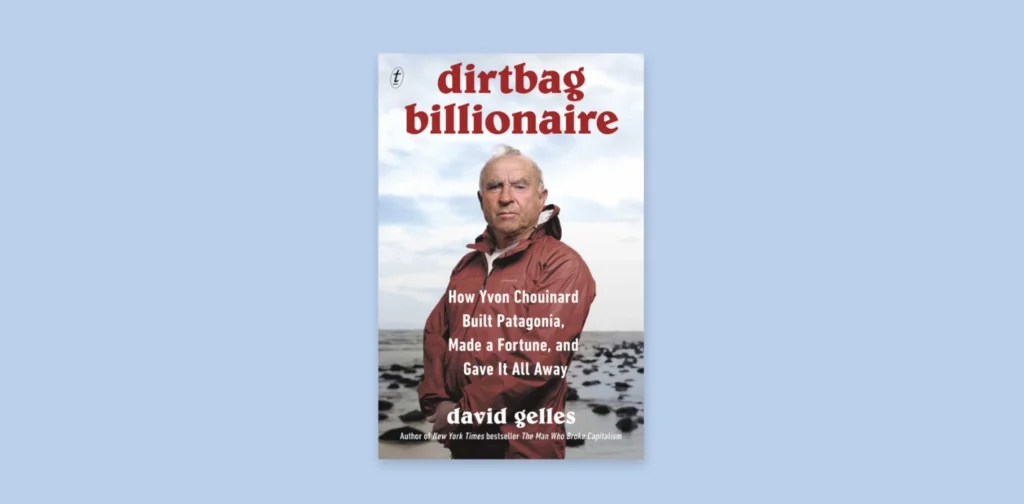

Dirtbag Billionaire: How Yvon Chouinard Built Patagonia, Made a Fortune, and Gave It All Away by David Gelles. | Publisher: Text Publishing Company (2025).

In 2017, Forbes magazine named Yvon Chouinard among its World’s Billionaire List with an estimated net worth of 1.2 billion USD. For most people, it would be the highest honor—a recognition of outstanding financial success. But for Chouinard, founder of Patagonia, it was “one of the worst days of his life.”

He considers the title an insult. This paradox—a billionaire who hates his wealth, a businessman who has never wanted to do business, an anti-capitalism’ capitalist’—is the core of the book “Dirtbag Billionaire: How Yvon Chouinard Built Patagonia, Made a Fortune, and Gave It All Away” by David Gelles.

Gelles, a climate correspondent at The New York Times, has won many prestigious awards. He is not a stranger to untangling the complexity of American corporate leadership. His previous book, “The Man Who Broke Capitalism”, dissects the systemic damage caused by Jack Welch at General Electric—the obsession with shareholder value that corroded long-term value in favor of quarterly profits. In Dirtbag Billionaire, Gelles serves the perfect counter-narrative: a story of a leader who rejects Welchian principles, purposefully stifles growth, wholeheartedly prioritizes the planet above profit, and—as the nail in the coffin—gives away all his wealth to save the Earth.

As someone who admires Chouinard and Gelles, there was no other book release that made my heart beat as fast. Before my copy arrived, I had read over 10 reviews and watched videos featuring Gelles as a guest. And, once the book was in my hands, nothing could stop me from reading it at once.

Dirtbag as Life Philosophy

The term ‘dirtbag’ is the highest form of praise in the hiking community. It refers to someone who isn’t very interested in materialism and is willing to sleep under the stars, in what modern society would deem dirty, just to be closer to the next hiking and outdoor adventure. Chouinard, born in 1938 to a modest family in Maine, USA, self-identifies as a lifelong dirtbag. His business journey began not from the spirit of entrepreneurship nor the pursuit of wealth. Instead, it started from the pure need to fulfill his hobby of being outdoors.

In 1957, Chouinard began forging steel pitons for climbing the steep walls of Yosemite Valley. He sold them out of his car trunk, not to generate profit but to fund his beloved surfing and climbing lifestyle. Among the contemporary business narrative full of ambitions of unicorns and billion-dollar exit strategies, Chouinard was an anomaly: a successful businessman who never even wanted to be one.

His leadership style was just as unconventional. He called it MBA—Management by Absence. Chouinard often left the office for months at a time to go on adventures, forcing and trusting his team to be independent. He never even graduated from college. In some cases, executives who were recruited from traditional management backgrounds failed to adapt to the ‘chaos’ of Patagonia’s culture.

Quality Evolution: From Functional to Ethical

The most defining moment of the story occurred in the 1970s. Chouinard realized that the steel pitons—which made up 70% of his earnings—had been scarring the rock walls of Yosemite Valley that he loved. Then, his decision was simple yet radical: he stopped producing the steep pitons and switched to the clean climbing techniques, using non-damaging aluminum chocks and stoppers. He sacrificed profit for purpose and value decades before corporate sustainability became a common jargon.

The decision became a template for the evolution of Patagonia’s quality philosophy. At first, quality meant functionality and durability. Over time, the definition evolved into something holistic and ethical: questioning the use of toxic materials, the impact of production on the planet, and working conditions at supplier sites.

In 1996, Patagonia completely switched to organic cotton after learning that conventional cotton production used pesticides and formaldehyde that harmed workers. This decision carried a huge financial risk as there was no supplier for organic cotton at the time. Still, Chouinard held fast.

The Worn Wear Program might be the most interesting manifestation of this philosophy. Patagonia encourages its customers to repair their products and, if there’s nothing else they can do, resell and recycle them. This paradoxical model promotes buying less, an antithesis to the conventional business model. For that, the iconic “Don’t Buy This Jacket” ad for the 2011 Black Friday led to increased sales. Patagonia has mastered the art of brilliant marketing that sells more by advocating less consumption.

Contradiction that Drives Innovation

I really like that Gelles did not let Dirtbag Billionaire fall into the trap of hagiography. He presents Chouinard not as a saint but as a complex, even contradictory character. Chouinard is an environmental activist with a clothing brand that he admits still pollutes a lot, despite efforts. He’s an anti-authoritarian idealist with years of military contract to produce tactical wear for Navy SEALS and Army Rangers. He’s a leader who has built a working culture that’s the best in the industry—with onsite childcare since 1983 and an employee retention rate of almost 100% for women—but has consistently refused to grant employees company equity.

This refusal to share its equity is a significant pain point in Patagonia’s story. Chouinard worries that if employees own company shares, they may make decisions that do not align with Patagonia’s long-term values due to short-term temptations. When Chouinard finally gave away the entirety of his company to a non-profit entity in 2022, some longtime employees felt betrayed—they felt entitled to participate in the wealth they had helped accrue.

Gelles believes that this contradiction is unsolvable. However, the tension pushes Patagonia to keep innovating and introspecting. Chouinard’s essay titled “Reality Check” in 1991 was honest: “Everything we make pollutes.” Yet, this confession wasn’t paralyzing. It became a catalyst for continuous improvement.

However, despite Patagonia’s reputation as a leader in corporate sustainability, Chouinard seems too ashamed to say that his company is sustainable. He consistently calls Patagonia “a responsible company”. He believes that all of Patagonia’s admirable efforts are a matter of social responsibility, a manifestation of its responsibility for the full impact it has on people and the planet. Patagonia’s inspiring reports are called “Impact Report”, with the 2025 version subtitled “Work in Progress”. This brutal honesty keeps Patagonia away from greenwashing.

Going Purpose over Going Public

Nonetheless, the book’s narrative reached its climax in 2022. Chouinard, at 84, created an ownership structure that the global corporate history had never seen before. Instead of selling or doing an IPO—which worried Chouinard would put Patagonia under pressure to increase, or even maximize, shareholders’ profits—he transferred his ownership to two new entities.

Patagonia Purpose Trust holds 2% of voting shares, serving as an additional layer of governance to permanently protect the company’s values. Holdfast Collective, a 501(c)(4) non-profit organization, holds 98% of non-voting shares and receives all of Patagonia’s profit—projected to reach 100 million dollars annually—to fight the climate crisis. Everyone, even those who had known of Patagonia’s journey like me, couldn’t help but be shocked. The famed announcement stated, “Earth is now our only shareholder.”

The decision to choose the 501(c)(4) structure instead of the traditional 501(c)(3) was crucial. C4 allows political contributions, opening the door for Patagonia to engage in policy advocacy. On the other hand, the Chouinard family wouldn’t receive the significant tax breaks they would’ve had from C3. They paid about 17.5 million USD to transfer their voting shares. Meanwhile, billions of dollars of equity value were never monetized or sold—therefore, no capital gain was realized.

Criticism and accusations that this move was a clever tax-cut scheme fell apart. The wealth of the Chouinard family really was all out for the Earth they loved. Gelles firmly distinguishes Patagonia’s transaction from cases like Barre Seid’s, in which he donated his company to a non-profit, which then sold it tax-free. Patagonia’s equity shares are never sold; its activism is funded by the sustainable profit flows from its business operations.

Model Limitation

The strength of Dirtbag Billionaire comes from its balance and honesty, which made me smile as I read it. Gelles never claims that Chouinard has solved the problems capitalism faces and causes. He explicitly admits that Patagonia’s success primarily comes from how Chouinard had controlled 100% of the ownership for decades. For many publicly owned companies, adopting Patagonia’s radical strategies is impossible under the pressure of Wall Street’s quarterly earnings. From limiting company growth based on supply chain capacity to provide socially responsible quality materials to spending 20% of company earnings (not profit!) on activism, it would be impossible.

The question of scalability and replicability is left unanswered. Most probably on purpose. Is Patagonia’s “purpose-driven capitalism” model adoptable by other companies? Or is it only possible under the unique condition of an idealist founder with complete control, a niche yet loyal market, and an unshakable commitment to one’s values?

Academic commentator Christopher Marquis sharply notes that, even with admirable sustainability achievement, Patagonia cannot run away from the fundamental contradiction of capitalism. Companies like Patagonia are still forced to participate in this extractive economic system. I think this book, no matter how balanced it tries to be, risks inflating hope on what Responsible Capitalism or Stakeholder Capitalism can achieve when, in reality, companies like Patagonia are needles in mountains of haystacks.

Dirtbag Billionaire and a Sustainable Legacy

At the end of the day, Dirtbag Billionaire is a case study of an extreme value-based leadership in the modern business landscape. Gelles successfully captured the essence of Chouinard—a dirtbag, an unwilling billionaire, a challenger of conventional business logic. The story contrasts with Jack Welch’s, who provides a powerful framework for understanding the spectrum of contemporary business leadership followed by the majority of those in top management today, with results that Chouinard hates.

Chouinard himself thinks that Patagonia’s biggest contribution is to be a role model for other businesses. He hopes that 50 years from now, Patagonia will be known as a food producer focused on regenerative agriculture and sustainable seafood—sectors he believes have the potential to actively heal the planet rather than merely minimize harm.

To me, Dirtbag Billionaire’s central message is that the corrective journey to sustainability demands diligence, not perfection. Chouinard, who now spends most of his time fishing, is done with his worldly affairs. He has made sure that his company will keep “doing the right thing” in the future—even when the definition of “the right thing” itself remains an unsolvable paradox that becomes a productive tension driving endless innovation.

In the world of business dominated by short-term maximization and maximum value extraction, Chouinard offers an alternative narration: business can, and should, be a force for good. Even with his path full of contradiction, chaos, and painful compromise, his steps are worth following. Chouinard and Patagonia’s story in Gelles’s book, which will surely be referred to for decades to come, is not a story of perfection—it is a touching and inspiring story about an honest and ongoing fight to do better at every turn.

Editor: Abul Muamar

Translator: Nazalea Kusuma

Join Green Network Asia Membership

Amidst today’s increasingly complex global challenges, equipping yourself, team, and communities with interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral insights on sustainability-related issues and sustainable development is no longer optional — it is a strategic necessity to stay ahead and stay relevant.

Jalal

Jalal is a Senior Advisor at Green Network Asia. He is a sustainability consultant, advisor, and provocateur with over 25 years of professional experience. He has worked for several multilateral organizations and national and multinational companies as a subject matter expert, advisor, and board committee member in CSR, sustainability, and ESG. He has founded and become a principal consultant in several sustainability consultancies as well as served as a board committee member and volunteer at various social organizations that promote sustainability.

A Major Cause of Changing Rainfall Patterns

A Major Cause of Changing Rainfall Patterns  Strengthening Disaster Risk Governance at Local Levels

Strengthening Disaster Risk Governance at Local Levels  Recognizing the Role of Local Communities in Biodiversity Conservation

Recognizing the Role of Local Communities in Biodiversity Conservation  Preserving a People’s Identity by Protecting Art and Cultural Heritage amid Conflicts

Preserving a People’s Identity by Protecting Art and Cultural Heritage amid Conflicts  Revealing Progress and Gaps of Healthcare in Southeast Asia

Revealing Progress and Gaps of Healthcare in Southeast Asia  Looking into Unregulated Mining along the Mekong River and Its Impacts

Looking into Unregulated Mining along the Mekong River and Its Impacts