Kristopel Bili Looks After Sumba’s Forests and Culture through Literature

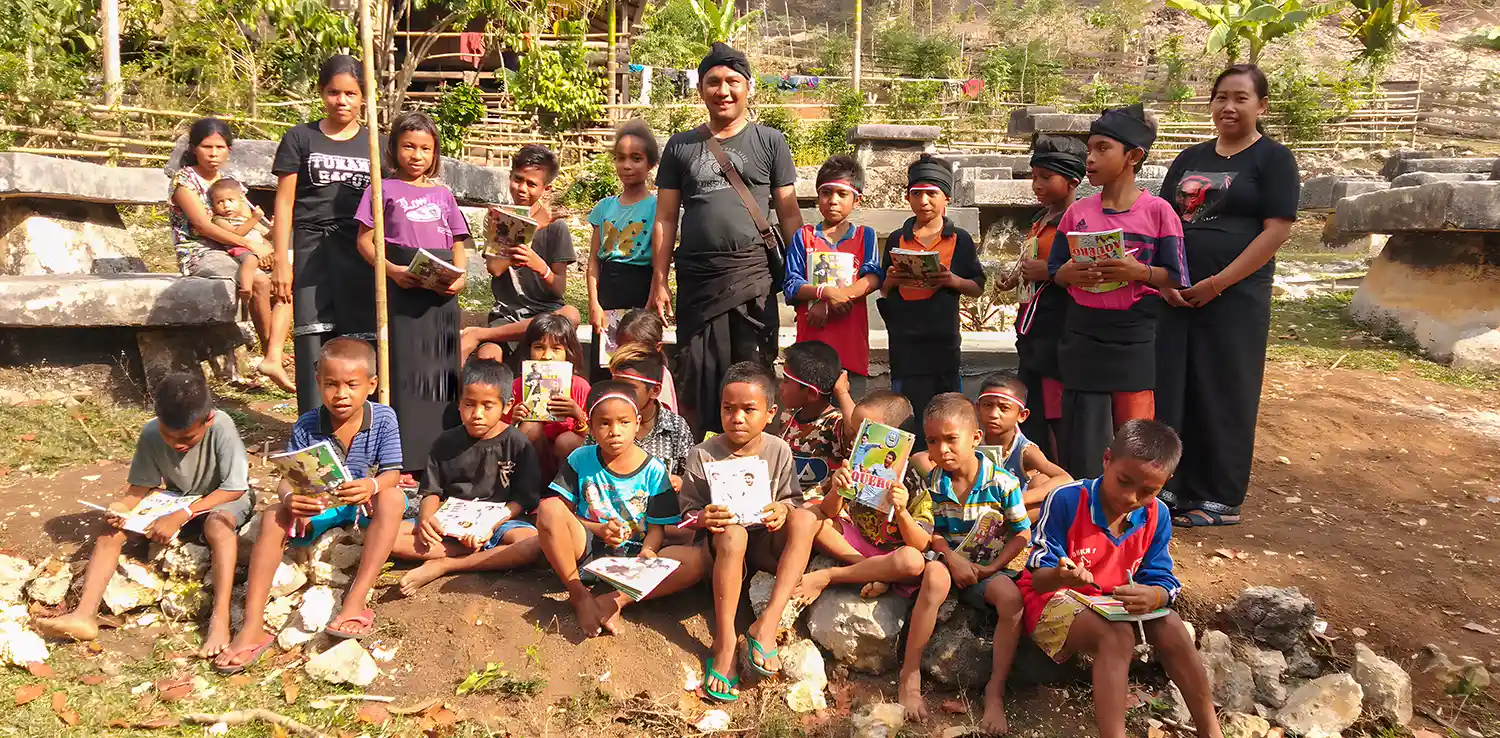

Kristopel Bili. | Photo: Kristopel Bili’s Personal Archive.

Culture is the foundation of life. Beyond traditions and heritages, culture keeps multiple aspects of life flowing in harmony, including our environment. Leaving culture behind might lead to disharmony, and eventually negatively impact our lives. For the Sumba-native Indonesian forest ranger Kristopel Bili, the thought of cultural degradation leaves him restless.

Sadly, Sumba Island, East Nusa Tenggara, is experiencing cultural degradation and persistent threat of deforestation, causing disharmony in the ecosystems.

As a forest ranger, Kristopel Bili sees the need for a more effective and impactful approach to overcome environmental degradation issues. He believes overcoming those issues doesn’t need violence or guns; it needs gentle words and culture.

Establishing Sakola Wanno to Revive Sumba’s Culture

Kristopel has been witnessing the cultural values in Sumba, Indonesia, eroding slowly for the past ten years, especially in the villages near the forests. Back then, older people in his village had the utmost respect for the existence of trees in forests and would never cut them down brutally and illegally.

“Back then, our elders would conduct rituals first to ask permission from the guardian spirits and ancestors before cutting down trees from the forests. And they would only cut enough trees according to their needs,” said Kristopel.

Kristopel lamented how some villagers have started to take out wood from the Indigenous forests to rebuild their houses that were caught on fire.

He continued, “But, as time passed, especially when many houses got caught in fire, the forests, including Indigenous forests, were destroyed. Logging becomes uncontrollable. These people no longer pay their respect to the cultural values in Indigenous rituals that are sacred and must be obeyed. Cultural degradation is happening here. It’s as if rituals are just ordinary ceremonies. We have lost the true meaning of culture.”

“We don’t have to take out the woods from the forests to build Indigenous houses. Our ancestors have taught us everything about life. Big trees have to be planted in the village, a stack of rocks (kangali) should be placed under the fences, then little forests (kalio’wo) below. These little forests or kalio’wo have been cleared and sold out. Meanwhile, they are the source of our wood, bamboo ropes, and rattan. What does this mean? Cultural degradation is happening here, even among the elders and Indigenous leaders,” said Kristopel.

The cultural degradation also affects various traditions in Sumba. Pasola is one of them. It is a tradition where two groups compete in a sports game of javelin throwing while riding horses. Pasola is a part of the Marapu – the belief of the Sumba people – ritual ceremony to celebrate the paddy planting season and ask for forgiveness and prosperity for the harvest.

The schedule for the Pasola performance is decided by calculating the position of the moon, stars, and other natural signs. A month before the ceremony starts, the people of the village must adhere to several prohibitions, including hosting parties and building houses.

“Now, whenever ‘special’ guests and foreign tourists are coming, [the Pasola performance] is no longer held according to the rituals taught and inherited by our predecessors. Instead, it will be adjusted according to the arrival of those ‘special’ guests and foreign tourists. It’s weird. I don’t know whose hand is at play here; the schedule is often brought forward and postponed. It’s no longer decided based on stars, constellations, or moon locations like the Indigenous leaders (Rato) used to do. It’s no longer sacred,” he said. “In big cities, cultural degradation happens because of modernization and technological development. Meanwhile, in Sumba, those things aren’t really evident, but the culture is still degrading.”

All those forms of cultural degradation pushed Kristopel to build Sakola Wanno in 2017. The name is derived from the local language, Sumbese. ‘Sakola’ means school, and ‘Wanno’ means village. Through the school, Kristopel wants to revive Sumba’s culture through art and literature.

His determination to build Sakola Wanno became more solid after reading a message carved on the coffin of Hendrik Pali, an East Sumba Indigenous figure, which he carried with several other people to the burial site.

“There was a writing that said ‘Jangan biarkan anak-anak tercabut dari akar budayanya.’ Do not let our children be yanked out of their cultural roots. While carrying the coffin, I felt the burden of culture on my shoulders get heavier. I wanted to instill character and culture education for children as early as possible so they wouldn’t get easily swayed,” said Kristopel.

Kristopel Bili on Shaping Children’s Characters with Literature

Every year, the number of Ana Wanno—the term used to call children who study at Sakola Wanno—increases. They are children from elementary, junior high, and high schools. Until 2023, 40 children are studying at Sakola Wanno, coming from Wanno Village, Puu Mangita, Dede Kadu Village, and other nearby villages. The children are enthusiastic about learning to read and write poetry, counting, and playing traditional games.

With the help of two other educators, Kristopel teaches children at Sakola Wanno to plant trees yearly, hold a ritual of blessings for water springs and release eels as the guardian of the springs, and properly develop agriculture farms and plantations. Among the trees planted are porang (elephant foot yam), avocado, banana, and durian. The tree planting also aims to achieve food sovereignty and improve local people’s welfare.

“The main priority is to sharpen their characters and minds as village kids so they can be brave and express themselves with conviction. So, when they move out of the village someday and go to Java, for example, they have confidence,” said the man born in Waikabubak on April 1, 1982.

Literature isn’t exactly Kristopel’s strongest suit. The man who graduated from the Faculty of Forestry, Yogyakarta Institute of Agriculture, was only introduced to literature after he finished college. In 2009, before going back to his village, Kristopel received a message that kept echoing in his head. The message was from Umbu Landu Paranggi, a Sumbanese writer who passed away on April 21, 2021. The message came to Kristopel through the writer’s daughter, Rambu Anarara Wulang Paranggi. “It said: Send me the creations of my children. Form a small community of literature and turn Sumba into poetry. Do not look for me; I will come to you in an endless longing,” said Kristopel.

“I hadn’t written a single poem that time. I hadn’t even met him; he was just entrusting his message to me. The words felt very powerful to me. At Sakola Wanno, we firmly believe in the power of words,” said Kristopel.

To fund Sakola Wanno’s activities, Kristopel and his wife willingly spare a portion of their paychecks every month. “Through literature, we can get to know ourselves, our culture, and our country, Indonesia, better,” he affirmed.

Empowering People with Entrepreneurial Training

Not only educating children, Kristopel also reaches out to adults in efforts to halt deforestation. In this case, he uses a different approach. While children are introduced to literature, Kristopel gives entrepreneurial training to adults to develop small businesses, such as in tea and coffee, through Tea Kandara and Coffee Wanno.

“Adults are harder to change, both mentally and in their characters. So, for adults, I use a populist economic empowerment. Because I see that environmental and cultural degradation happen due to the economy I believe they won’t cut down more trees when the economy improves,” said Kristopel.

Besides Sakola Wanno, Kristopel also established a performing art and culture group for Sumbese culture, Seni Sastra Budaya Sumba (SBSS), with a similar purpose. He wants the youth of Sumba to cultivate love and appreciation for nature and culture.

For everything he has done so far, Kristopel doesn’t hope for anything except for Sumba’s environment and culture to continue flourishing. He doesn’t even budge when people call him crazy for doing what he does. Kristopel hopes that the government and other stakeholders can take concrete, serious, and effective steps to save Sumba’s environment and culture.

“There are so many postponed dreams I want to realize, especially for the Sumba culture. I don’t want to be rich with material things, that’s for sure. I want to feel rich from my abundant and concrete work. But this dream needs support. I hope I’m not alone in this,” he concluded.

Editor: Nazalea Kusuma

Translator: Kresentia Madina

The original version of this article is published in Indonesian at Green Network Asia – Indonesia.

Co-create positive impact for people and the planet.

Amidst today’s increasingly complex global challenges, equipping yourself, team, and communities with interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral insights on sustainability-related issues and sustainable development is no longer optional — it is a strategic necessity to stay ahead and stay relevant.

Abul Muamar

Amar is the Manager of Indonesian Digital Publications at Green Network Asia. He holds a Master’s degree in Philosophy from Universitas Gadjah Mada and a Bachelor’s degree in Communication Studies from Universitas Sumatera Utara. He has over ten years of professional experience in journalism as a reporter and editor for several national-level media companies in Indonesia. He is also a writer, editor, and translator with a particular interest in socio-economic and environmental issues.

Reframing Governance in the Era of Water Bankruptcy

Reframing Governance in the Era of Water Bankruptcy  Strengthening Resilience amid Growing Dependence on Space Infrastructure

Strengthening Resilience amid Growing Dependence on Space Infrastructure  Indian Gig Workers Push Back Against 10-Minute Delivery Service Strain

Indian Gig Workers Push Back Against 10-Minute Delivery Service Strain  Call for Governance: Grassroots Initiatives Look to Scale Efforts to Conserve Depleting Groundwater

Call for Governance: Grassroots Initiatives Look to Scale Efforts to Conserve Depleting Groundwater  Integrating Environment, Climate Change, and Sustainability Issues into Education Systems

Integrating Environment, Climate Change, and Sustainability Issues into Education Systems  Finally Enforced: Understanding the UN High Seas Treaty

Finally Enforced: Understanding the UN High Seas Treaty